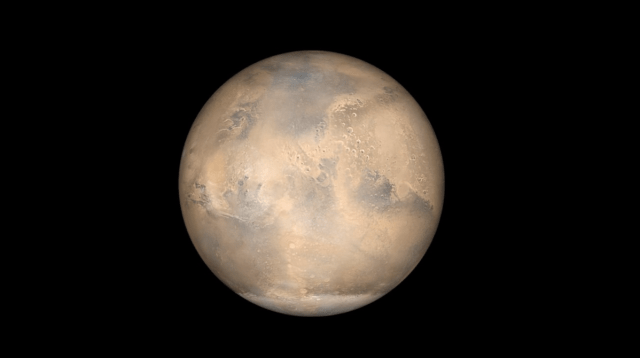

Researchers from Cornell University have shed light on the mysterious bright radar reflections initially thought to indicate liquid water beneath the ice cap on Mars’ south pole. Their findings suggest a simpler explanation involving ice layers and radar interference.

The study, led by Daniel Lalich, a research associate in the Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, challenges the notion of liquid water on Mars. While not ruling out the possibility entirely, the team proposes an alternative mechanism that doesn’t require such a dramatic interpretation.

The Radar Reflection Puzzle

Robotic explorers have provided evidence of ancient water flow on the Martian surface, including at a former river delta currently under investigation by NASA’s Perseverance rover. In 2018, the European Space Agency-led Mars Express orbiter’s science team announced the discovery of a buried lake below the south polar cap using ground-penetrating radar.

The implications were significant: If there’s liquid water, there could be microbial life. However, Lalich and his team argue that the bright radar reflections observed may not necessarily indicate liquid water.

Constructive Interference and Ice Layers

The researchers conducted simulations to explore how small variations in layers of water ice could lead to radar reflections. These variations, too subtle for ground-penetrating radar instruments to resolve, can cause constructive interference between radar waves. Essentially, radar waves bouncing off closely spaced ice layers may combine, amplifying their peaks and troughs.

Lalich explains, “We’re showing that there are much simpler ways to get the same observation without having to stretch that far, using mechanisms and materials that we already know exist there.”

A More Complete Story

The team’s new research provides a more comprehensive explanation, closing gaps in the radar interference hypothesis. They generated thousands of layering scenarios based on conditions known to exist at the Martian poles. These scenarios varied the ice layers’ composition and spacing, mimicking what would be expected over tens or hundreds of miles.

The result? Bright subsurface signals are consistent with observations made by the Mars Express orbiter’s MARSIS radar instrument. Lalich emphasizes that this thin-layer interference model explains the entire population of observations below the ice cap without introducing anything unique or odd.

Liquid Water on Mars?

While Lalich doesn’t rule out the possibility of future detections by more capable instruments, he suspects that the story of liquid water and potential life on Mars ended long ago. “The idea that there would be liquid water even somewhat near the surface would have been really exciting,” he says. “I just don’t think it’s there.”